New Delhi August 20; Faith and disbelief, God and atheism, caste and equality are twinborn foes. When one is born, the other rises to challenge it. Even as the Vedic tradition was consolidated, atheism emerged in ancient India, as chronicled by Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya. When Thiruvalluvar asked in his Thirukural, ‘What is the purpose of knowledge if one did not worship at the feet of God’ he was conceding that there were indeed scholars who thought otherwise.

New Delhi August 20; Faith and disbelief, God and atheism, caste and equality are twinborn foes. When one is born, the other rises to challenge it. Even as the Vedic tradition was consolidated, atheism emerged in ancient India, as chronicled by Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya. When Thiruvalluvar asked in his Thirukural, ‘What is the purpose of knowledge if one did not worship at the feet of God’ he was conceding that there were indeed scholars who thought otherwise.

Knowledge progresses with questioning. A society bereft of questions and smug in its received wisdom can only be sterile. Even as organised religion thrived, feeding on royal patronage and legitimising social inequality, the other tradition survived.

Sithars, the rebel songsters of Tamil Nadu living outside the pale of society, asked blunt questions: ‘What is this mantra / you mumble within your mouth / going round and round / a planted stone,/offering it flowers?/ Can a planted stone talk/when the Lord is within you?/ Can the pot and the spoon feel the taste/of food cooked in them?”

“Will the rains fall only for a few/and exclude others? /Will the winds discriminate/against a few? /Will the earth refuse to bear the weight of a few? /And the sun refuse to shine on some?” asked a latter-day Kapilar in a famous akaval poem.

A 15th century Dalit girl of Paichalur, Uttaranallur Nangai, who had fallen in love with a Brahmin boy, challenged the villagers who came to torch her alive: “I saw a tuft/on the heron’s head/and a wattle/on the head of a hen. /I saw a flabby tail. /I saw fire on water. / So do not talk/of the four Vedas/saying that you belong/to a superior caste.”

Written canons tried to silence such voices, but they were kept alive among people, transmitted orally across generations. In the 19th century, western-educated intellectuals influenced by Enlightenment thought drew on these traditions to buttress modern egalitarian ideas. The rediscovery of Buddhism strengthened the rationalist arsenal. Lower-caste ideologues such as Athipakkam Venkatachala Nayakar and Ayotheedas Pandithar were rooted in this heterodox tradition. If the Bengali Brahmo Samaj appeared to be tame in the context of Tamil Nadu, the credit should go to this tradition.

Even Subramania Bharati wrote in his last years that the smritis and the epics are but ‘figments of imagination meant to impart morals.’ When his follower Bharatidasan espoused Periyar’s rationalist ideals, the critically-inclined short story writer Pudumaippithan silenced obscurantists by asking if he was any more radical than the Sithars.

One of the early publications of Periyar’s rationalistic Self-Respect Movement was a selection of Vallalar Ramalinga Swamigal’s poems. Vallalar’s radical denouncement, ‘Let blind custom be buried in the earth’ figured prominently in the book. Tamil translations of Bhagat Singh’s Why I am an Atheist and Lenin’s On Religion too came out from Periyar’s press.

In 1943, when C.N. Annadurai declared that ‘let the fire spread’ and called for the burning of Kambar’s Ramayanam and Periya Puranam, god-believing Tamil scholars Somasundara Bharati and R.P. Sethu Pillai met Anna on the platform. Word was matched by word, and idea by idea. Not by bullets and blood.

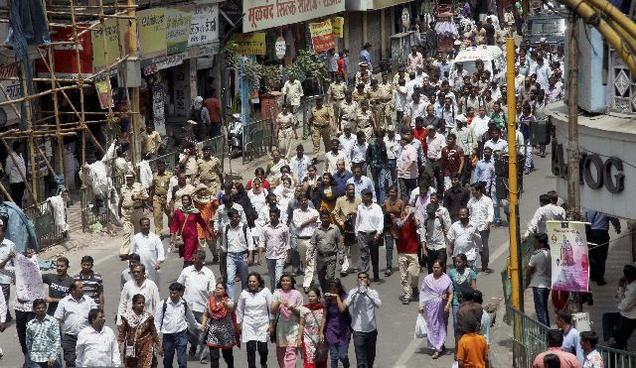

Not every atheist holds an Oxford Chair like Dawkins. Vallalar disappeared under mysterious circumstances. The rebel of Paichalur was lynched. Bullets may have riddled Narendra Dabholkar’s body. But words, songs, and ideas yet live.

(The poems quoted in this article draw from a forthcoming book of Tamil Siththar poems translated by M.L. Thangappa and edited by A.R. Venkatachalapathy to be published by Navayana. chalapathy@mids.ac.in))