Bangalore; September 01: It is not just malnourishment that is plaguing the urban poor. Non-communicable lifestyle diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, which are usually associated with the wealthy, are now affecting the urban poor in city slums.

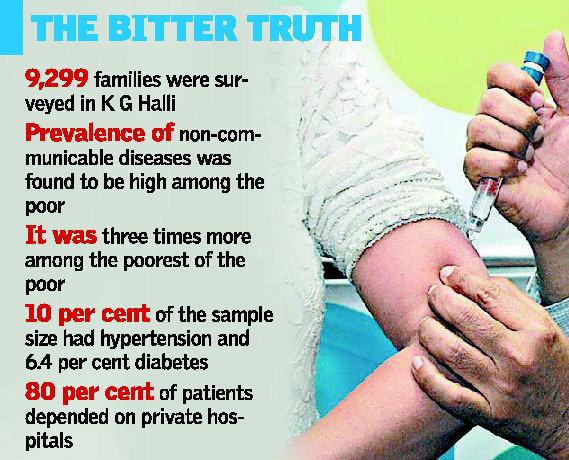

A recent study by a team of researchers from the city has found a high prevalence of chronic (non-communicable) diseases among residents of Kadugondanahalli (K.G. Halli). Interestingly it was found that the prevalence was significantly high (three times more) among the poorest of the poor.

The team led by Upendra Bhojani from the city-based Institute of Public Health (IPH) took up the study to assess the prevalence of chronic conditions (non-communicable diseases) and the health-seeking behavior of the residents.

Published on August 13 in BioMed Central (BMC) Health Services Research, an international medical journal, the study involved a house-to-house survey covering 9,299 households (44,514 individuals). “We relied on self-report by respondents to assess the presence of any chronic conditions, including diabetes and hypertension,” explained Dr. Bhojani.

Chronic conditions

While the study found that the overall prevalence of self-reported chronic conditions was 13.8 per cent of the sample size among adults, hypertension (10 per cent prevalence) and diabetes (6.4 per cent) were found to be the most commonly reported conditions. “We found that older people and women were more likely to report chronic conditions. Our study suggests a reversal of socio-economic gradient with people living below the poverty line at significantly greater odds of reporting chronic conditions than people living above the poverty line,” Dr. Bhojani said.

The team found that private healthcare providers managed over 80 per cent of the patients in K G Halli. A majority of patients— 42.9 per cent of the sample size — were managed at the clinic, health centre level. While 38.9 per cent of patients visited referral hospitals, 18.2 per cent of the patients took treatment at super-specialty hospitals. An increase in income was positively associated with the use of private facilities

“Elderly people, people below the poverty line and those seeking care from hospitals were found to use government services. Our findings provide further evidence of the urgent need to improve care for chronic conditions for urban poor, with a preferential focus on improving service delivery in government health facilities,” Dr Bhojani said.

An earlier study, conducted by Dr. Bhojani’s team in the same area and published on November 16, 2012 in BMC Public Health, had revealed that 69.6 per cent of the 9,299 households surveyed made out-of-pocket payments for outpatient care. This amounted to 3.2 per cent of their total income

Heavy borrowing

Following this, 16 per cent of the households suffered financial problems by spending more than 10 per cent of household income on outpatient care.

“Unable to cope, families borrowed money (4.2 per cent instances) and sold or mortgaged their assets (0.4 per cent instances),” he said.

“This study provides evidence that out-of-pocket payment for chronic conditions, even for outpatient care, pushed people into poverty. Our findings suggest that improving availability of affordable medications and diagnostics for chronic conditions, as well as strengthening the gate keeping function of the primary care services are important measures to enhance financial protection for urban poor. The findings call for inclusion of outpatient care for chronic conditions in existing government-initiated health insurance schemes,” Dr Bhojani added.

HND